Plugin Links:

Navigation Information

You can navigate within this module using the Back and Next buttons on this page. However, using the internet browser's Back and Next buttons will remove you from this course.

HUD Exchange - Getting to Work: A Training Curriculum for HIV/AIDS Service Providers and Housing Providers - Module 1

You can navigate within this module using the Back and Next buttons on this page. However, using the internet browser's Back and Next buttons will remove you from this course.

Use the Back and Next buttons on the bottom left of the screen to move one slide forward or backward. You can use the Table of Contents button to navigate to the Table of Contents slide. Use the unit links on the Table of Contents slide to navigate directly to any unit. The home button will take you to the opening slide for this module.

For users on a Mac, scrollbars will only appear after you begin scrolling. With the cursor in the content to be scrolled, a user must make a two-finger upwards gesture; this will make a small gray bar appear on the right-hand side. The user can either continue with the two-finger gesture, swiping up to scroll down or swiping down to scroll up, or can click the gray bar and drag it up or down. Note: Mac users can also opt to have scrollbars visible at all times by going to System Preferences, clicking on General, and then selecting "Always" under the "Show Scroll Bars" option.

This module is the first in a three-part series. In it, we will explore the many reasons why people living with HIV/AIDS are choosing work, and why service providers should help them consider and achieve their employment goals.

Employment can be critical to improving the economic and personal well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). It can impact health and can increase a person's ability to live a satisfying, productive and meaningful life. Employment can also increase financial self-sufficiency and reduce reliance on publicly funded benefits and other services.

This module, titled Understanding the Value of Employment, will explore the many reasons why service providers should assist People Living with HIV or AIDS with developing and pursuing their employment goals. It is the first of a three-part series and provides a broad foundation for Module 2, Adopting an Employment and Training Mindset, Individually, and Organizationally and Module 3, Incorporating Employment into the HIV/AIDS Service Menu.

Employment can be critical to improving the economic and personal well-being of people living with and most at risk of HIV or AIDS. It can impact health and can increase a person's ability to lead a satisfying, productive and meaningful life. Employment can also increase financial self-sufficiency and reduce reliance on publicly funded benefits and other services.

To effectively assist people living with HIV or AIDS as they consider, prepare for, or obtain employment, it is important to have a strong understanding of how the HIV/AIDS epidemic has changed over the years and the role employment can play in the lives of People Living with HIV or AIDS. You should also understand how employment is a key consideration within a holistic approach to addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its place in larger national priorities.

This module, titled Understanding the Value of Employment, will explore the many reasons why service providers should assist People Living with HIV or AIDS with developing and pursuing their employment goals. It is the first of a three-part series and provides a broad foundation for Module 2, Adopting an Employment and Training Mindset, Individually, and Organizationally and Module 3, Incorporating Employment into the HIV/AIDS Service Menu.

After completing Module 1: Understanding the Value of Work, you will be able to:

Use the below links to go directly to each section or specific slide.

In the years following the first diagnosed cases in the U.S. in the early 1980s, HIV/AIDS spread rapidly. The public response was initially slow and limited. Many scholars and advocates have documented the inadequacy of early public health, treatment, and research efforts, commonly believed to have resulted from the association of HIV/AIDS with sexual behavior and marginalized populations. By 1989, when the number of reported AIDS cases had reached 100,000, researchers ascertained that HIV spreads throughout the body long before AIDS symptoms develop. Thus the focus of treatment shifted to suppressing HIV viral load levels.

Gay-related immune deficiency - offhandedly called the gay plague - was the 1982 name proposed to describe what we now call AIDS. A number of risk factors and groups were quickly identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among them male homosexuality, intravenous drug use and hemophilia. As diagnoses increased, a variety of advocacy and support services for those affected began to be put in place, particularly in San Francisco and New York City. At the time, these support services primarily entailed grief counseling and personal support for individuals who were sick or dying.

In these early days, HIV and AIDS were met with significant stigma and discrimination, predominantly because of the association of the virus with sexual behavior, especially among gay or bisexual men, as well as intravenous drug use. Some individuals with HIV or AIDS were shunned by friends and relatives. Customers avoided restaurants for fear that gay waiters would spread the virus. Some parents, fearing their children might get AIDS from infected classmates, kept their children out of school. In fact, many HIV/AIDS service provider organizations were established in response to the extreme and profound discrimination faced by people living with HIV or AIDS when they sought - but were often refused - services in the general community. Largely due to the populations most affected, the response to HIV and AIDS was slow and limited, at both the community and national levels.

In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law, providing federal civil protections to people with disabilities similar to those provided to other groups with a history of discrimination. People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) are covered under its provisions, which address five key areas, the first of which is employment. The mid-1990s saw further medical breakthroughs, and the number of deaths from AIDS in the U.S. began to decline significantly. PLWHA in the U.S. were increasingly able to lead healthy, long lives and pursue personal and professional goals in a way not previously possible. Today, significant progress continues to be made, both in treatment and prevention.

Ryan White, a teenager with AIDS in Indiana, spoke up for all infected individuals and became a national hero before his death in 1990. Shortly thereafter, in 1990, another milestone was reached - this time legal. The Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA, was signed into law. The ADA provides federal civil protections to people with disabilities similar to those provided to other groups with a history of discrimination. People living with HIV or AIDS are covered under its provisions, which address five key areas, the first of which is employment.

The mid-1990s saw further medical breakthroughs, and the number of deaths from AIDS in the U.S. began to decline significantly. Although no cure had been discovered, a turning point was reached. People living with HIV or AIDS in the U.S. were increasingly able to lead healthy, long lives and pursue personal and professional goals in a way not possible a decade before. Today, significant progress continues to be made, both in treatment and prevention. As a result, the nature of HIV/AIDS service provision continues to evolve.

2 out of 10 are women

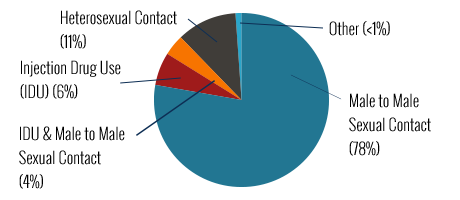

61% of newly infected individuals are men who have sex with men

27% of new infections are individuals infected through heterosexual contact

9% of new infections are people who are injection drug users

1715 per 100,000

8 times higher than among whites

585 per 100,000

3 times higher than among whites

224 per 100,000

The epidemiology of HIV infection in the United States has shifted since the early 1980s, when new infections were reported predominantly in large West and East Coast cities among young, White, middle-class men who have sex with men (MSM). Today, the epidemic has a broad geographic distribution and affects individuals of all ages, sexes, races, and income levels, and multiple transmission risk behaviors. Data from: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/52/suppl_2/S208.full

These same data show that women represent 23% of estimated new HIV infections. Transgender individuals are also at high risk for HIV infection, with preliminary data indicating rates occurring at almost 3 times that of non-transgender men and almost 9 times that of non-transgender women.

Recent data (2009) indicate that gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men remain the most severely affected (61% of new infections) while individuals infected through heterosexual contact (27% of new infections) and people who are injection drug users (9% of new infections) are also severely affected.

Since the 1990s, both male and female African American and Latino populations have been disproportionately affected by HIV. HIV prevalence among African Americans (1715 per 100,000 population) was almost 8 times higher than among Whites (224 per 100,000 population). The overall prevalence rate for Latinos (585 per 100,000 population) was nearly 3 times the rate for Whites (224 per 100,000 population).

Many PLWHA today have employment service needs that are very different from those of PLWHA in the early years of the epidemic. Early efforts at providing employment services for PLWHA were designed to promote the continued workforce participation or reentry of individuals who, given the demographic profile of the epidemic at the time, tended to be white, well-educated men with previous employment experience.

For some PLWHA today, the goal is workforce entry, not reentry. Studies reveal limited work experience and a need for assistance in gaining

interpersonal or "soft skills in addition to specific job skills among people with HIV/AIDS. Many of the communities most affected by or at risk for HIV/AIDS are also those that experience higher rates of discrimination and other employment barriers, such as a history of drug use and/or incarceration.

A 1992 study of Multitasking Systems (MTS) of New York, Inc., one of the first employment and training programs in the U.S. for PLWHA, found that HIV is frequently not the primary vocational impediment for PLWHA. Poverty, homelessness, discrimination, lack of job

skills and low literacy, conditions that predated development of HIV-related functional limitations, were the primary impediments to employment.

More information about this and other studies that address outcomes for employment of PLWHA will be discussed later in the module.

Today, the national response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic is supported by a strong policy agenda and several federal initiatives, which recognize the importance of employment considerations for PLWHA. Employment is a key component of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, HIV Care Continuum Initiative and Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.

On July 13, 2010, President Obama released the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, the nation's first-ever comprehensive plan for responding to the domestic HIV/AIDS epidemic. Six federal agencies, including the Department of Labor (DOL) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), are charged with advancing the goals of:

The National HIV/AIDS Strategy includes specific action steps related to employment of PLWHA, including addressing stigma and discrimination as barriers to workforce participation. The importance of employment to the overall strategy reflects the changing nature of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the reality that addressing the employment needs of PLWHA is a critical component of all three strategic priorities.

The work of HIV/AIDS service providers is critical to the National HIV/AIDS Strategy's success, on multiple levels. Assisting clients in preparing for and/or obtaining employment is increasingly among the ways they contribute.

White House Office of National AIDS Policy Launches HIV Care Continuum Initiative Video.

Many people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. are not getting the full benefits of care and treatment available. In fact, only slightly more than 1 in 4 make it through what is referred to as the "Care Continuum." For every 100, it is estimated that:

In response to this "treatment cascade," in July 2013, President Obama directed the National HIV/AIDS Strategy's lead agencies to accelerate efforts to increase HIV testing, enhance linkage and engagement in care, and advance treatment outcomes. Increasing employment for people living with HIV/AIDS clearly support the goals of this "HIV Care Continuum Initiative," because research indicates a positive correlation between employment and health. Furthermore, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is significantly expanding health insurance options for people living with HIV/AIDS, thereby increasing access to care and treatment.

In 2010, the 19-member U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) released the nation's first comprehensive Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. This plan, titled Opening Doors, provides a strategy for aligning mainstream housing, health, education and other human services to prevent and end homelessness. The plan's vision is centered on the belief that "no one should experience homelessness—no one should be without a safe, stable, place to call home."

One of the objectives for this plan is to increase economic security for people experiencing or most at risk of homelessness. Employment is clearly a critical component of ending homelessness. HIV/AIDS and housing service providers have a powerful role in advancing the Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness and the National HIV/AIDS strategy by offering employment services to individuals who are, or may be at risk of becoming, homeless.

Quiz

An episodic disability is characterized by fluctuating periods and degrees of illness and wellness. It may wax and wane over time, often with unpredictability. Examples of episodic disabilities include multiple sclerosis, lupus, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, and many forms of mental illness.

HIV/AIDS has become an episodic disability for many people. It is important for PLWHA, like all people with episodic disabilities, and all people for that matter, to make informed decisions when seeking work, whether doing so for the first time or after a period of unemployment or underemployment.

Although many PLWHA can work, some may have specific challenges and considerations they should take into account, and many of these are similar to those faced by people with other disabilities, especially episodic disabilities.

Some of these challenges and considerations may include depression, medication side effects, and periods of fatigue and other symptoms. Some PLWHA have ongoing limitations related to the virus and co-existing disorders, while others' health and functioning fluctuate over time. However, many PLWHA experience normal health and functioning and, with proper support, can manage their conditions and successfully maintain employment as well as pursue other professional and personal interests.

Like people with other episodic disabilities, the key to being able to successfully maintain employment for some PLWHA is flexible work arrangements. Typically, such arrangements include adjustments to job place, time or task. For PLWHA, this might mean being able to take time off during the work day for medical appointments or periodic breaks due to fatigue.

Some PLWHA might choose to seek employment (or self-employment) that is flexible by nature, such as part-time work or alternative scheduling (for instance, an early or late shift or working remotely) that allows them to manage their condition as necessary when not working.

Flexible work arrangements might also be requested as reasonable accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) or other

disability nondiscrimination laws, or facilitated under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) or state-level family and medical leave statutes.

Given the nature of an episodic disability, a person experiencing one may move in and out of the workforce. This can create challenges because the criteria for eligibility for disability benefits includes an inability to work on a long-term basis. This issue, including relevant laws and regulations, will be addressed in more detail in Modules 2 and 3 of this course.

In addition, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) increases employment options for PLWHA and other disabilities by expanding access to health care, eliminating annual or lifetime benefit maximums, and prohibiting discrimination by insurers based on pre-existing conditions.

Requesting workplace accommodations raises issues of disclosure. It is important to know that:

Due to a history of stigma and discrimination, many people living with HIV or AIDS may hesitate to request workplace accommodations because they are not willing to disclose specifics about their condition to their employer. It is important for people living with HIV or AIDS to know that they are not required to disclose their condition to their employer in order to request accommodations, just as people living with any other disability are not required to do so. In many cases, it is possible to disclose not that one has HIV or AIDS in particular, but rather that one has an episodic condition that requires time off for medical appointments or breaks to deal with medication side effects or fatigue.

Quiz

Research has long shown a correlation between employment and economic, social and health benefits. In recent years, this body of research has expanded to include studies focused specifically on PLWHA. Although these studies have all approached the issue from different angles, they collectively point to the value of employment services as a component of holistic HIV/AIDS service provision.

Employment has been positively linked to improved physical and behavioral health and thus can play an important role in reducing health disparities - differences in health that are closely linked with social, economic and/or environmental disadvantages. Health disparities adversely affect groups who have historically experienced discrimination or exclusion based on characteristics such as

race/ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, gender, gender identity, age, mental health, disability, sexual orientation or geographic location. Several of these groups are also among those most affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Research on the impact of employment on the health of PLWHA is still in its early stages, and there remains a need for longitudinal research from which to draw long-term conclusions. Furthermore, as with all research, sampling methodologies and the definition of variables - for example, what even constitutes employment - vary widely.

Nevertheless, an evidence-based argument for offering employment services is emerging.

For more information about these research studies, as well as others that point to the value of employment for people living with HIV/AIDS, download "Research Findings: A Closer Look at Employment and PLWHA.

This 1992 study of Multitasking Systems (MTS) of New York, Inc., assessed the first employment and training program in the U.S. for PLWHA. MTS was a demonstration project funded by the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA). Titled The Impact of HIV on Employment: a Retrospective Analysis of the Characteristics of Persons with HIV Disease Seeking Job Placement Services, it was conducted by Sandy DeRobertis, MTS's project director from 1991 to 1993. The population reviewed was 385 PLWHA served by MTS between March of 1989 and April of 1992.

The principal finding was that HIV is frequently not the primary vocational impediment for PLWHA. Rather, poverty, homelessness, discrimination, lack of job skills and low literacy, conditions that predated development of HIV-related immunodeficiency functional limitations, were the primary impediments to employment for those PLWHA seeking services from MTS - not HIV/AIDS. This study also revealed that PLWHA who continued to work were less susceptible to depression and lived longer than those who disengaged, providing an early indication of the potential role of employment for PLWHA.

This study explored the employment needs and experiences of PLWHA in the U.S., taking into consideration a range of demographic variables. It was conducted in 2008-2009 by Dr. Liza Conyers in collaboration with the National Working Positive Coalition (NWPC) and the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute.

Among the survey's respondents, 32 percent were employed. Among these, 63 percent worked full time, 26 percent worked part time and 12 percent worked less than 14 hours per week. Among employed participants who were unemployed prior to their current job, specific findings related to CD4 counts, medication adherence, alcohol and drug use, and unprotected sex, suggested that working may positively impact health and reduce health risk behaviors.

The OHTN Cohort Study (OCS) is a multi-site research study that collects clinical and socio-behavioral data on a group of participants living with HIV over time. This unique research database is governed by PLWHA in Ontario and used by scientists, community-based researchers and other stakeholders.

In 2011, researchers published the first of several OCS studies exploring the relationships between employment and the physical and mental health of PLWHA.

The study summarized in this article explored the relationship between employment status and health-related quality of life for PLWHA by analyzing baseline data provided by 361 participants in the OCS. Specifically, it used regression analysis - a process for estimating the relationships among different variables - to evaluate the contribution of employment status to both physical and mental health quality of life measures. The analysis showed that employment status was strongly correlated with both physical and mental health quality of life after controlling for potential confounding variables. The correlation was stronger with physical health than mental health.

Allison Webel, Doctor of Philosophy, Registered Nurse, and Patricia Higgins, Doctor of Philosophy, Registered Nurse, both of Case Western Reserve University, conducted 12 focus groups with 48 women, exploring the key social roles associated with positive HIV self-management in women. Six predominant social roles emerged: employee, pet owner, mother/grandmother, faith believer, advocate and stigmatized patient. The first five roles had a positive impact on HIV self-management.

The role of stigmatized patient, however, was not associated with improved HIV self-management. In fact, this role contributed to fear of disclosure and thus a decreased likelihood of seeking out available supports.

Quiz

Ken Wampler, Founder and Executive Director, the Alpha Workshops

PLWHA, like people with a range of other conditions, have tremendous but often undervalued or underdeveloped skills and talents. With encouragement, commitment and support, they can gain confidence in their prospects for putting these skills and talents to work, leading to an enhanced quality of life and potentially improved health outcomes. Today, employment is a key component of serving the whole person. The links on this slide provide more information about topics discussed in Module 1:

Congratulations! You have completed Module 1 of the Getting to Work Training Curriculum, Understanding the Value of Work. This module highlighted the importance of focusing on the employment of people living with HIV/AIDS. It also described the changing nature of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S., identifying medical advances, social changes, and federal initiatives to support PLWHA in employment and housing. Finally, it addressed HIV/AIDS as an episodic disability before concluding with a summary of some of the research that has shown the benefits of employment for PLWHA. Building on this knowledge, Module 2 of this curriculum will focus on employment services for PLWHA and how they are delivered.

Please proceed to Module 2, Adapting an Employment and Training Mindset. Upon completion of all three modules, you can complete a quiz to earn a certificate of completion.

The U.S. Department of Labor and U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development would like to acknowledge the following organizations and agencies for their substantial contributions to

this project:

In addition, we would like to thank the numerous individuals - members of the HIV/AIDS community, HIV/AIDS service provider community, researchers, government personnel, and advocates - who reviewed content, were featured in videos, and/or whose work in the area of HIV/AIDS and employment provided the foundation for content herein.

Slide ${num} of ${total}

${module} > ${unit} > ${page}